DIRECTIONS: Using your lightbox, choose FOOD as your subject matter. The food is your choice. Be clever and unexpected with the set-up and arrangement, and as with the first group of photos you made, vary the placement of your lights to create distinctly different shadow/highlight, angle, etc.

BEFORE STARTING:

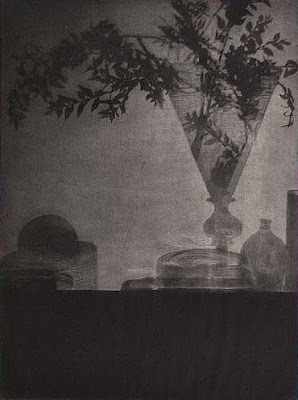

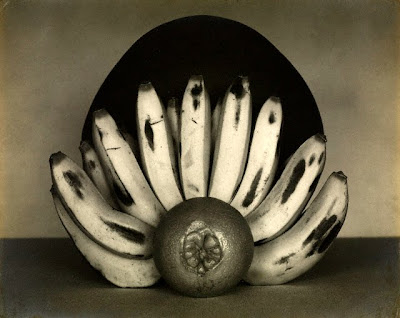

Get inspired by conducting a "photography" search of food still life. Refine the search with "clever"/"modern"/"unusual"/"traditional"/"beautiful"/etc.

Also, peruse the links provided in previous posts.

A GREATER CHALLENGE:

How can you take something that you find/see, borrow from it, and then make it your own?

BEFORE STARTING:

Get inspired by conducting a "photography" search of food still life. Refine the search with "clever"/"modern"/"unusual"/"traditional"/"beautiful"/etc.

Also, peruse the links provided in previous posts.

A GREATER CHALLENGE:

How can you take something that you find/see, borrow from it, and then make it your own?